A year ago, as I set out to explore the life of Alice Balfour and her moths, I didn’t give much thought to what I might find or where it might lead. I wanted to discover more about the moths she encountered and was interested to learn more about the pursuit of natural history in the Edwardian era, but mostly I was starting ‘a project’ to add purpose to my own everyday moth recording in East Lothian. Making lists of moths from different sites is all very well, but it is much more rewarding to put these lists into some sort of context. Scientific or otherwise.

Whittingehame lies just a few miles from the coast near Dunbar in one direction and almost scuffs at the foothills of the Lammermuirs in the opposite direction. Some varied habitats to amuse a natural historian within easy striking distance. However, the Estate itself is less obviously appealing, predominantly a mixture of farmland broken up by areas of young-ish woodland. Without the lure of Alice’s footsteps it wouldn’t be the first place I’d choose to look for moths. But Maple Pug, an unusual moth in Scotland (now known from just 4 sites) was found in the arboretum in June. Surprises are of course part of the fun of moth trapping, by definition turning up when you are not expecting them, but just as importantly Whittingehame has had little if any moth recording attention since Alice’s time, so most of the moths I found there this year represent either new or ‘modern’ dots on the moth map – all valuable information in the quest to understand the changing fortunes of wildlife in the UK. If only for the moths I recorded there this year, the project has been worthwhile.

Meanwhile, at National Museums Scotland’s Collections centre I spent time looking at and enjoying Alice’s moth specimens and notebooks. I have become familiar with the black-inked handwriting of her labels (our modern typeface approach may have benefits, but just isn’t the same) and admired her skills at setting and pinning. The most recent specimens I have noted were from July 1935. Alice was by then 86 years old and I can only hope I will at least still be up for trying to record moths, should I reach that age. Initially I assumed all her specimens would be correctly identified and displayed in the correct drawers, but as I became better at relating pinned specimens to the living thing and developed a more critical eye it became clear some specimens didn’t quite match the appearance of their drawer-mates. Some errors may have been introduced many years ago when specimens were re-curated from Alice’s cabinets into the museum’s ones; others were probably mis-identifications by Alice or those whose expertise she sought. I have come to appreciate even more how lucky we are with the identification resources and expert help that is so easily accessible to modern-day moth enthusiasts.

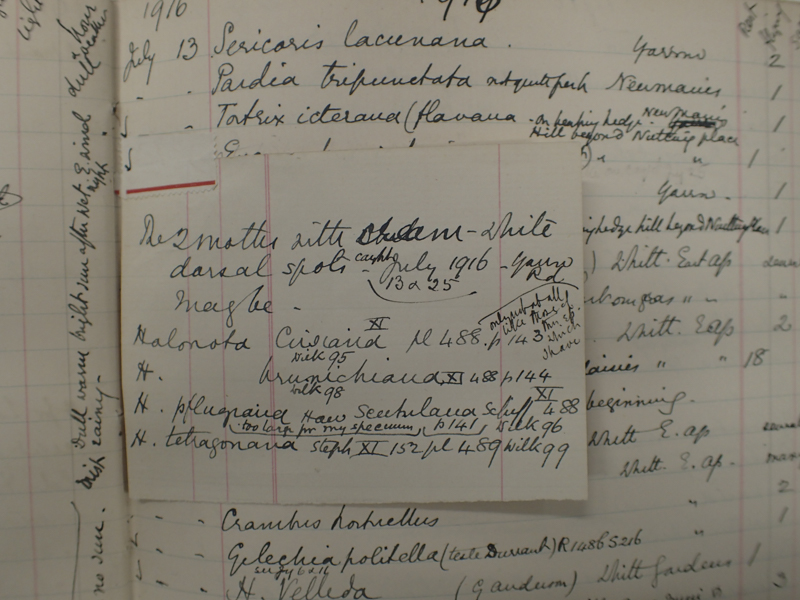

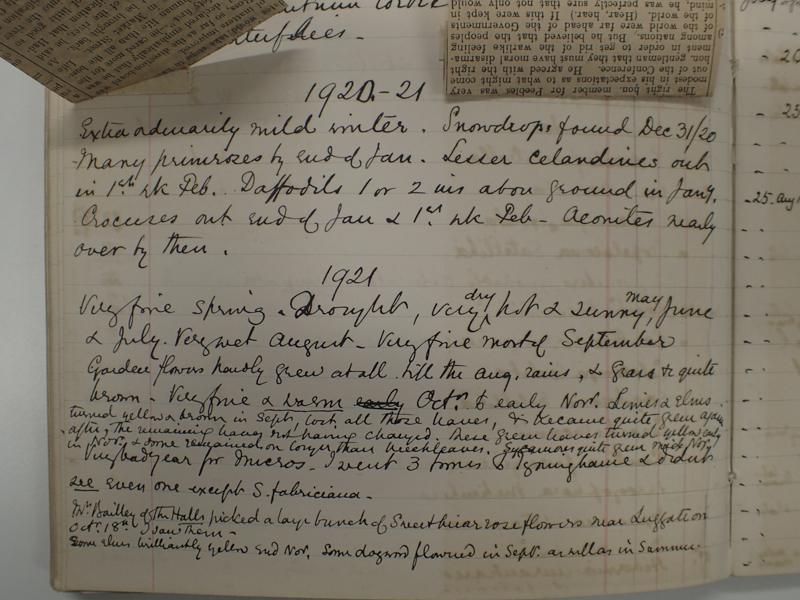

In Alice’s notebooks, I am getting better at recognising no-longer used names for some species: Cidaria was the genus ascribed to many of her carpet-type moths; nowadays just one UK moth, Barred Yellow, retains it. I have learned how such name-changes can lead to mis-identification, mistakes that can persist without sufficient knowledge or the specimen to clear up any doubt. In between Alice’s species lists I can see evidence of self-doubt in her identifications. There are entries in pencil, question marks, and incomplete names where only the genus is recorded, for example for the notoriously tricky ‘Eupithecia’ or ‘Scoparia’. Sometimes she returns to these entries later, adding the name of the species along with a respected authority who helped her identify it. Using the date and location details, usually leads back to a specimen if an identity check is needed. Descriptive paragraphs and annotations to her lists show she wasn’t merely after a long list of species, but was thinking about what she was finding and how and why it varied from year to year. It will be interesting to see if her seasonal observations differ to more recent records.

My investigations have also led to accounts from nieces, sisters-in-law and others in which brief glimpses of Alice’s personality are shared. From these there is an impression of a fondly-loved but at times exasperatingly hard to get on with woman. In a family of high-achieving siblings it seems she often felt she fell short of the mark, inwardly at least lacking in self-confidence. She took her domestic duties of managing the Estate very seriously and was a stickler for lists and rules and detailed instructions. I wonder if she knew how to relax?! Her loyalty and sense of duty in supporting the political career of her eldest brother Arthur was strong and certainly came well above any moth-ing activity. In fact there are very few moth specimens for the period 1880 – 1910 in her collection and it wasn’t until after this, when she was entering her 60s and Arthur’s premiership was over, that her obsession with moths came to the fore. She grumbled about her domestic duty giving her “no free time”, but perhaps she enjoyed the responsibility and sense of purpose this role provided?

Aunt Alice was a wonderful housewife and organiser, but not by nature a Martha. The Balfour love of science was strong in her…. She had no mean gifts as an artist, but she was much too alive to the difference between the amateur and the professional to take much pleasure in her own drawings.”

Blanche Dugdale, in Family Homespun 1940

Alice’s moth legacy is notable in that she seems to have only sought specimens caught in East Lothian. This focus was unusual, especially for somebody not restricted by means or travel. Despite spending long periods of each year in London, there are neither moths nor mention of moths from here. She had good friends in England who were keen collectors, yet no indication that she went moth hunting when visiting them. In her account of travels in South Africa she mentions garden plants (another keen interest), but not butterflies or moths and although her brothers looked out butterflies and moths for her collection when they were studying in England, there is no trace of these. Most moth collectors of her time wanted a showy collection with as many different species they could find, swapping specimens with others or even buying in the hard to get ones. There is no evidence Alice joined such frivolities. Although this more parochial approach may have be unusual, I can relate to it. Moths discovered in my home county (both by me and others) are generally far more exciting than those found elsewhere and my own moth activities further afield are limited without too much of a grudge by whether I can fit a trap into the luggage on the annual family holiday. Maybe this will change as I age. For Alice, perhaps it was only at Whittingehame that she felt she had sufficient time and space to indulge in her hobby. Perhaps she preferred to be thorough in a restricted area and leave other places to other people. Year after year she diligently records mostly the same species in her notebooks. She seems to have been driven much more by a desire to document in detail the moths around Whittingehame than to impress others with a long species list.

Pale -shouldered Brocade

Feathered Thorn

By focussing only on Alice’s moth activities it is easy to think moths were the most important part of her life. Her collection at the museum has close to 10,000 specimens, including several unusual species I would love to see. She combined her own records with those of other local moth enthusiasts and published a paper on the butterflies and moths of East Lothian. This provides an unusually comprehensive record of the moths in the region a century ago, with accompanying details that few other UK collectors or collections from that time provide. She corresponded and exchanged ideas with other scientists showing an intelligence and attention to detail that could have served her well in academic life. Despite this most of her time was taken up managing her Estate, organising (or as one niece put it “arranging”) people and supporting others’ work. She was an important part of many busy lives and entertained and was entertained by some of the most influential people of the time. Plenty of interesting and intellectual stimulation, but by no means restricted to entomology.

Moths were a hobby, albeit a hobby which she took as seriously as everything else in her life. Her interest was as much, if not more, in the science as in the collecting: she sought to understand and explain. Largely self-taught, with no formal training or mentoring, she relied on guide books such as Barrett’s multi-volume tome “The Lepidoptera of the British Islands” to identify her catches. Sometimes she asked local friends for help with her identifications, but mostly it seemed she worked alone, enjoying the challenge, encouraging others and accepting that sometimes she couldn’t put a name to what she had seen. The excellent condition and labelling of her specimens is a testament to her high standards. Do we have it too easy these days, with instant internet access and and quick responses to identification queries? Does the process of trying to work it out for yourself, then changing your mind, before changing it back again make you a better naturalist? Only when she was organising her collection with a view to donating it to the museum did she send the trickiest specimens down south to be named by acclaimed experts in London. Even they didn’t always get it right, but was she too trusting to even consider questioning them? Although the errors are few, it has taken nearly a hundred years and somebody with enough time and interest, for these to be noticed and rectified.

Having got this far, I will continue to explore Alice’s moths and the places she frequented to find them. There is still much I can do and so much more I can find out. However, if there are lessons both me and Alice can to learn from her moth collection so far, they are the importance of keeping good notes and to have the confidence to query an identification that doesn’t look quite right.

Pingback: Pick & Mix 41 – some links to entertain and inform | Don't Forget the Roundabouts